Uncovering Hidden Treasure: Henrry and Maria’s Story

What Henry Hopkins, 35, lacks in stature, he more than makes up for in personality and determination. The small, energetic man is not afraid of hard, physical work or responsibility. He will do whatever is necessary to be able to provide for his family: his wife, Maria, as well as three sons and two daughters.

Henrry’s Childhood

“Life has always been hard for us,” he says, matter-of-factly, as if he never expected anything else. Hard work and poverty are all Henry had ever known. He was born into a family of day laborers. Both his mom and his dad worked other people’s land and lived in rented or loaned structures wherever they could.

For Henry, life was difficult but bearable until his parents separated when he was 10. To this day, he cannot talk about that time without tears welling up in his eyes and his voice beginning to quiver. “I don’t like to remember that time,” is all he manages to get out before tears start to stream down his face.

Maria shares the result of his parent’s divorce: Henry’s mother went to the city, Henry stopped attending school after finishing just his primary education, and he eventually went to live with his uncle, who showed him at a young age how to fend for himself by working in the fields.

Starting a Family

He met Maria and they started a family. They had three boys Kevin, now 16, Elton, now 14, and Henry now 12. They wanted to have more children, but had a hard time even providing for the needs of their three boys so they stopped, hoping their situation would improve, eventually. But, their situation did not improve; it couldn’t without land.

Like their parents before them and other landless farmers, Henry and Maria rented plots of land from large landowners to be able to grow their own food (paying their rent in a share of the crop). They also worked as day laborers on other nearby farms to earn cash for the things they needed but couldn’t grow, like soap, salt and oil. As harvests can be unpredictable and work hard to find, they lived day-by-day, never knowing where their next meal would come from, when they would have the chance to work again or who would loan them land next year.

Life With Agros

Today, things are different. “At least we have food and a house our life is stable,” says Henry. “Thanks to Agros and God, we have changed a lot,” says Henry, with a big smile, noting that access to land has been the biggest change. “The most important change is we have somewhere to live and some where to work,” he says. “Today, we have a treasure,” he says. “The land is our hidden treasure,” says Henry.

But, Henry realizes that although the land is a treasure, it would have been like a diamond trapped deep inside a mine, invisible and of almost no immediate help to him or his family without the appropriate tools and additional support from Agros to be able to access it. [Agros] gave us a house, they helped us bring water, they are helping us be able to diversify our crops.” He says this with a smile, as he boasts that he was able to harvest 4,000 pounds of beans this past season, thanks to improved agriculture techniques.

The Future

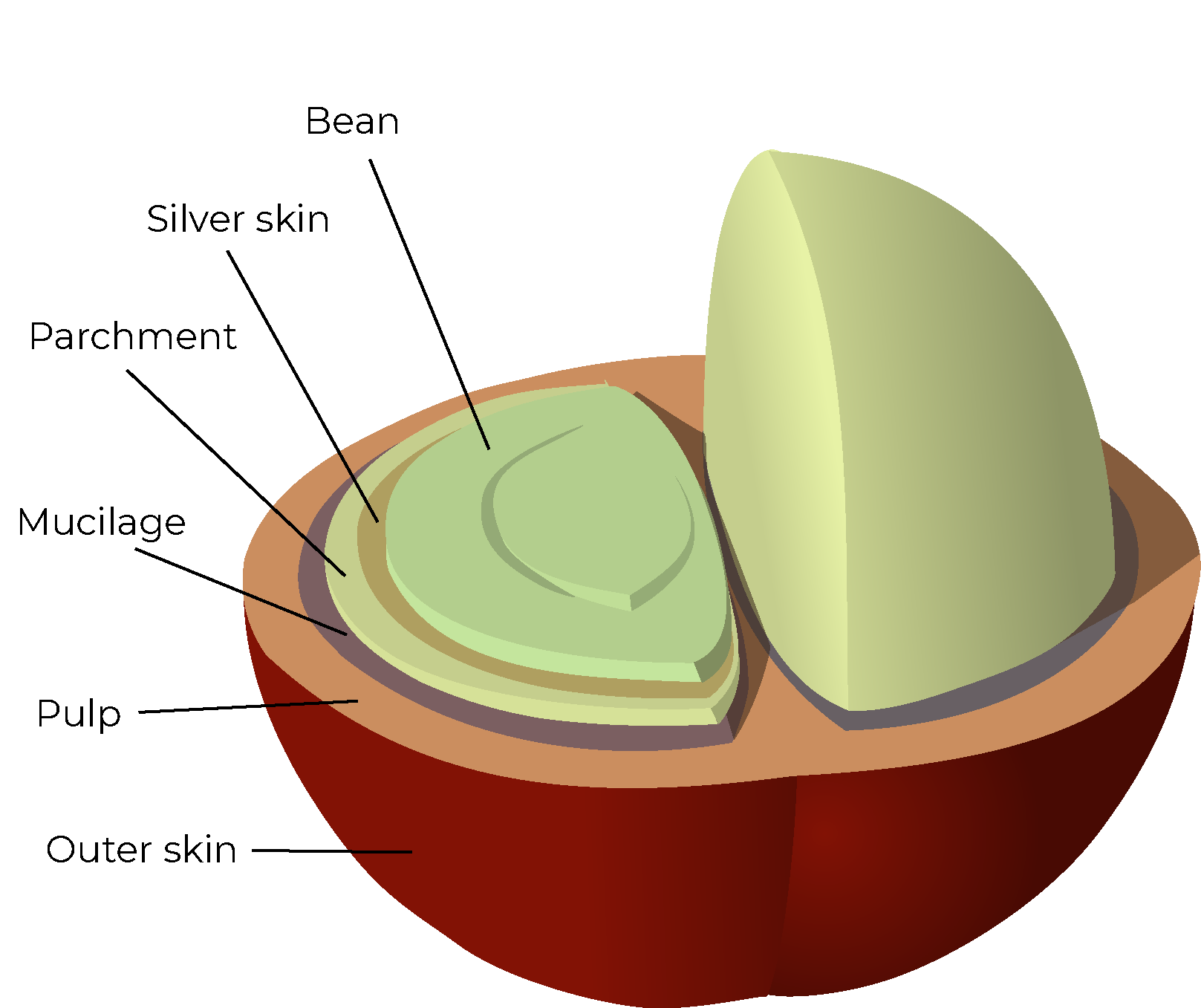

Today, Henrry is excited and optimistic about the future. He enjoys learning from Agros agricultural technicians who teach him and other partners how to plant, care for and harvest more lucrative crops; like cacao, rice and coffee. “So far I have only planted one part of my land with coffee,” he explains, excited and anxious to harvest his first crop in the coming months. “I love to work with coffee,” he says. “It is a crop that can earn you lots of money. If I am able, I want to change all my land over to coffee,” he says, explaining that he already has the next group of coffee plants growing in his nursery.

Henry cannot say enough good things about his experience with Agros and he doesn’t have to. The work speaks for itself as Henry who is part of the community’s board of directors knows well. People come all the time and say, “Help me Henry, I know about Agros. How can I be part of this community?”

Tierra Nueva

Henry’s life is not the only one that has improved. He shares how “It’s not just me. Here there are 150 families here in Tierra Nueva, the whole community is improved. We have land, somewhere to live, and support to be able to continue working. The only thing we are missing is electricity.”

Because of his family’s increased stability and improved outlook on life, Henry and Maria decided they could grow their family again as well. Since joining Agros, they have added two beautiful girls, Urania 2.5 years old and Marisol, 6 months old, to their family. “We needed them,” he says with a smile.